Has there ever been more pressure to have a full and luscious head of hair? Whether it’s dating app snaps, Instagram selfies, or even that corporate headshot on LinkedIn, maintaining a youthful appearance has become a critical feature of modern life.

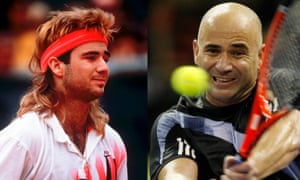

Writing in his autobiography, the tennis player Andre Agassi described his hair loss as a young man as like losing “little pieces of my identity”. With such anxieties magnified by the digital world, it’s little wonder that the impact of male and female pattern baldness has been increasingly linked to various mental health conditions.

Dr Coen Gho, founder of the Hair Science Institute – one of the world’s leading hair transplantation clinics with centres in London, Paris, Dubai, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Amsterdam and Maastricht – has little doubt that the different lifestyle choices and pressures that come with millennial existence contribute heavily to concerns around hair loss.

“Young people are more conscious about their appearance than ever before,” he says. “One particular contributory pattern that we’ve seen is that people are having serious relationships much later compared to 20 or 30 years ago. Now men are looking to find a partner in their 30s, which makes male pattern baldness more of a problem, as it tends to begin between the ages of 20 and 25.”

But despite the prevalence of hair loss – male pattern baldness affects approximately 50% of men over the age of 50, while around 50% of women over the age of 65 suffer from female pattern baldness – a drug capable of stopping it in its tracks has so far proven elusive.

Medical texts dating back to 1550BC reveal that the ancient Egyptians tried rubbing pretty much everything into their scalps, from ground donkey hooves to hippopotamus fat, in a bid to halt the balding process. These days, the two most prominent medications are minoxidil and finasteride, but both are only marginally effective at halting the rate of hair loss and cannot stop it completely. In addition, both drugs have unpleasant side-effects, with finasteride being unsuitable for women and known to induce erectile dysfunction in some men.

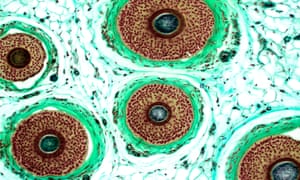

One of the main reasons we lack an effective way to prevent hair loss is that we still understand bafflingly little about the molecular mechanisms that underpin human hair growth and loss. Each hair follicle on our scalp is a miniature organ, which follows its own rhythmic cycle of growth, regression and rest throughout our lifetimes. With age, some of them become sensitive to hormones on the scalp, most notably dihydrotestosterone or DHT, which binds to the follicles and miniaturises them until they no longer produce visible hair. However, we know hardly anything about how this miniaturisation process happens, or how to prevent it.

According to Prof Ralf Paus, a dermatologist at the University of Manchester, this is because hair loss is still viewed largely as a cosmetic problem, rather than a disease. Because of this, in the western world, neither industry nor academic funding bodies have been willing to spend substantial sums of money on hair research. Despite the scale of patient demand, they have been dissuaded by the knowledge that any drug that hits the market is unlikely to be covered by the NHS or insurance companies.

“If you look at the sums pharma companies have spent on coming up with new cancer or heart disease drugs, this is in the billions,” Paus says. “These investments have just not been made into serious hair research.”

Though hair loss may have an undoubtable psychological impact on sufferers, it can’t be compared with chronic life-threatening diseases, many of which are incurable.

But there is increasing hope for those experiencing hair loss, as while we’re no closer to finding a way to prevent balding happening in the first place, scientists are developing increasingly novel and ingenuous ways to either replace or regenerate the lost hair.

The next generation of transplants

With no drug to prevent your hair from falling out, cosmetic surgery has looked to fill the void. Over the past two decades hair transplants – which take hair follicles from DHT-resistant “donor areas” at the back and sides of the scalp and relocate them to cover up bald patches – have offered new hope for hair loss sufferers.

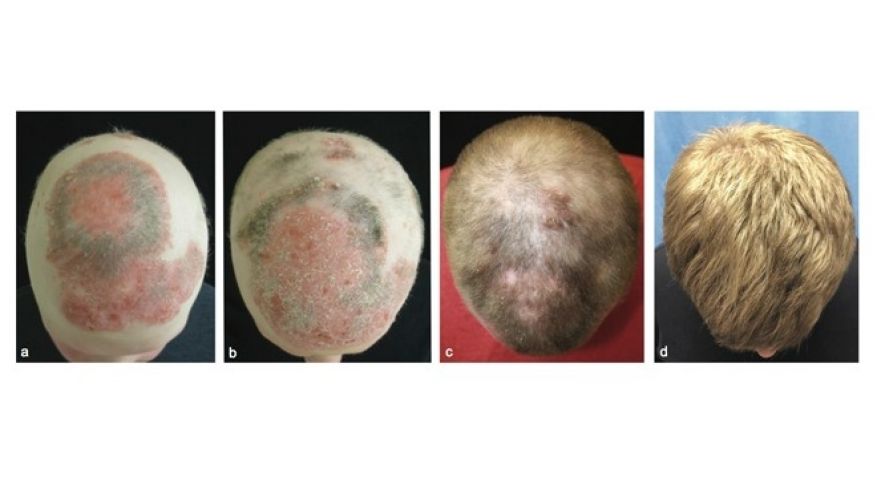

Such is the demand that market analysts have predicted the value of the global hair transplant industry will exceed $24.8bn (£20.3bn) by 2024, and the techniques are becoming increasingly advanced. Gho has pioneered a method called partial longitudinal follicular unit extraction, which extracts only a small portion of each hair follicle. This means that the patient isn’t left with scarring on the back and sides of their head, a serious risk with some traditional transplant procedures, which remove strips of skin and graft them into the bald area.

“We discovered that you don’t need the whole follicle, only a very small part, to produce a new hair to be transplanted into the recipient area,” he explains. “This means that after the treatment, the hairs in the donor area can be cut short, without any, or with minimal, visible density loss.”

Despite such advances, one of the current limitations of hair transplants is that many patients tend to require more than one procedure if they continue to lose their hair. Patients who are completely bald may also lack sufficient follicles on the back and sides to cover the bald areas on top.

Generating new hair from scratch

Instead of relying on donor hair, the way forward could be to use patient stem cells to grow whole hair follicles completely from scratch in the lab. These follicles could then be grown in unlimited quantities, and grafted on to the scalp. Many of these initiatives are taking place in Japan and South Korea, where such research is being bankrolled by either the government or private companies.

“There’s more investment in hair research in Korea and Japan, I think due to cultural differences,” explains Ohsang Kwon, a dermatologist at Seoul National University hospital. “In the western world, a lot of men will shave their head when they lose their hair. It is awkward to do this in our culture because it looks like a sign of a criminal or gangster.”

In the past year, a number of Japanese research groups have published reports that hint tantalisingly at a major breakthrough. At Yokohama National University, scientists led by Junji Fukuda have developed an experimental method for generating new hair follicles from stem cells in far higher quantities than ever before, while later this year, scientists at the Riken Centre for Developmental Biology will launch one of the first ever clinical trials with hair follicles grown entirely from stem cells.

“We definitely hope that stem cell approaches will be a better option for severe hair loss patients who do not have sufficient hairs for hair transplantation,” says Fukuda. “Traditional hair transplantation doesn’t increase hair numbers in the scalp, but hair-regenerative medicine can do in principle, by growing stem cells outside the body.”

In the future, 3D printing could even help do this on a large scale. At Columbia University in New York, Angela Christiano is working on creating “hair farms” using a grid of 3D-printed plastic moulds which mimic the exact shape of hair follicles. One of the major challenges faced when using stem cells to grow new hairs in a dish is that without the natural cues provided by the scalp, the cells don’t initially realise what they’re meant to do. Growing them in an artificial, hair-like environment helps stimulate them to make a hair, but scientists still have to solve some aesthetic challenges.

“We now need to tackle some key questions, such as: what colour will the hair be?” she says. “How do we make it pigmented? Is the patient’s hair straight or curly, and how do we create that texture when growing them in a grid? We need to solve these questions before we can think about injecting them into patients’ scalps.”

It all offers the potential to eliminate baldness for good. But Paus cautions that we still don’t know whether such methods would be safe, or end up being cosmetically pleasing. And even if they are, the cost will probably mean that they’re only accessible to the very rich.

“In reality there are many, many problems which mean I don’t see it working quite yet,” he says. “If you create a new mini-organ from scratch, you need to be extra careful that this organ doesn’t grow out of control and become a tumour. It also needs to grow in a way that looks natural.”

Reviving existing follicles

Rather than trying to grow completely new follicles, Paus thinks we should focus our efforts on trying to revive the ones we already have. He points out that even completely bald individuals still have 100,000 hair follicles all over their scalp. You just can’t see them.

“They’re miniaturised, so instead of making a normal long hair shaft, they only make a tiny, microscopically visible one,” he says. “But the organ is still there. So in order to solve the balding problem, we don’t need a single new hair follicle, we just need to get the ones already there to do their job properly again. If we could retransform these miniaturised follicles into big ones, we wouldn’t need a single hair transplant.”

Over the last four years, Paus has been exploring one particularly innovative way of doing this. There are a small handful of drugs, such as the immunosuppressant cyclosporine, which cause unwanted hair growth as a side-effect. By studying this, Paus’s research group has identified a completely new pathway for stimulating hair follicles.

“This [has] allowed us to discover some basic hair-growth control principles which could be used to find a completely new class of hair drugs,” he says.

They have since found a series of compounds that appear to be highly effective at stimulating this pathway and inducing hair growth when tested on human hair follicle cells in the lab. If safe enough, they could soon be trialled as a new topical treatment in volunteers.

As a result, while the holy grail of hair loss – preventing it completely – still remains a distant vision, there are enough promising treatments in the pipeline to allow even the baldest individuals to dream of new hair.

For scientists, especially those in the western world, the hope is simply that such breakthroughs will encourage new investment in the field.

“Hair is one of our most important social communication instruments, so new treatments are a huge market, a multimillion-dollar market that keeps growing,” says Paus. “There’s a vast economic potential from serious breakthroughs in hair research. But there needs to be more funding from government and industry to make them happen. That realisation hasn’t really happened yet.”

[“source=theguardian”]