New Delhi, India – Days after India banned the export of pharmaceuticals amid the coronavirus pandemic, it reversed its decision after US President Donald Trump last week demanded New Delhi ship anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) to the United States.

Foreign policy experts in India expressed shock at Trump’s threat of retaliation against India – a close trade and security ally of the US. But New Delhi’s decision to export HCQ seems to have changed the US president’s tune immediately.

“Extraordinary times require even closer cooperation between friends. Thank you India and the Indian people for the decision on HCQ. Will not be forgotten! Thank you Prime Minister @NarendraModi for your strong leadership in helping not just India, but humanity, in this fight!” tweeted Trump.

Earlier, the US president, while speaking to reporters, had called Modi “terrific” and said the US will “remember” that India allowed what they had requested.

Modi was quick to respond, underlining the close ties between the two countries.

“Fully agree with you President @realDonaldTrump. Times like these bring friends closer. The India-US partnership is stronger than ever. India shall do everything possible to help humanity’s fight against COVID-19. We shall win this together,” Modi tweeted.

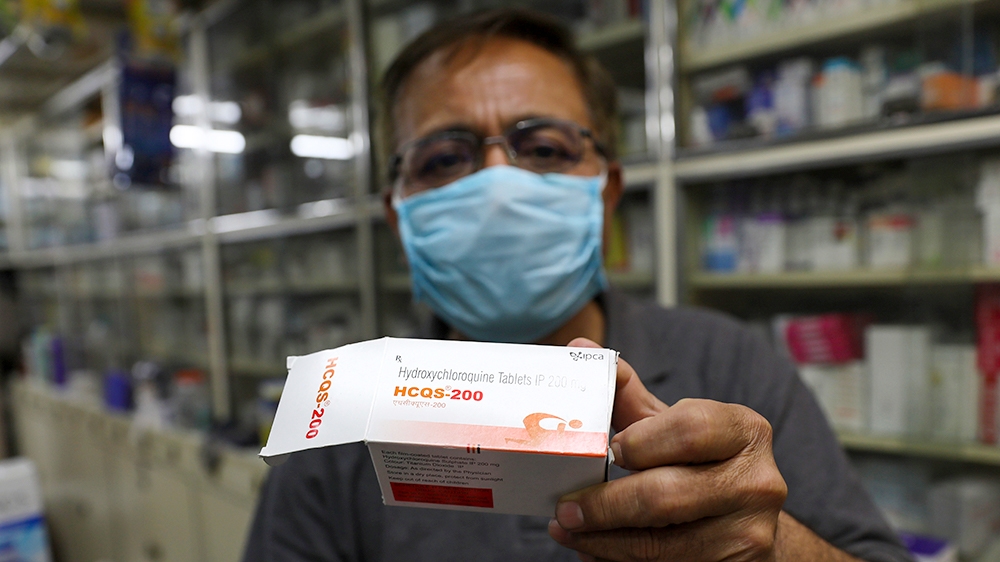

‘Game-changer’ drug

Trump, who has faced criticism for his handling of the COVID-19 crisis domestically, has called hydroxychloroquine a “game-changer” drug in the fight against coronavirus.

Global rush for HCQ forced India to put restrictions on its export and that of several other drugs on March 25. The only exceptions were on humanitarian grounds or for those who had made their advance payments in full.

Used for treating rheumatoid arthritis and malaria, India is one of the largest producers of HCQ in the world and exports $50m worth of it every year.

After the revocation of the ban, reports claimed that India has decided to export HCQ and other drugs used for treating COVID-19 patients to more than a dozen countries under two categories – humanitarian aid and commercial supply.

India, dubbed “the pharmacy of the world”, has drawn praise for the decision to export pharmaceuticals to some African and Latin American countries on humanitarian grounds.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu thanked Modi after New Delhi decided to ship the medicines.

Several other countries, including the United Kingdom, expressed their gratitude, earning diplomatic goodwill for New Delhi.

Ever since the coronavirus outbreak worsened, Modi has been constantly reaching out to the heads of states to create solidarity in fighting the pandemic.

In mid-March, Modi proposed a coronavirus fund for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries, with New Delhi committing $10m.

India will also send drugs to neighbouring countries such as Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles.

Will drug diplomacy work

The jury is still out on whether these efforts will strengthen India’s diplomatic position.

“In some terms, this decision has earned some goodwill. People are aware that unlike China which has a surplus of PPEs [personal protective equipment] or ventilators and the machinery to produce a lot of these things, India is making genuine sacrifices to show international solidarity and not to earn money,” Kanwal Sibal, India’s former foreign secretary, told Al Jazeera.

According to Sibal, these gestures will help India earn goodwill but it still remains a much smaller part of the overall scenario of how developing countries are going to relate to each other after the coronavirus pandemic is brought under control.

“So, I don’t think one should exaggerate the amount of goodwill but certainly India’s diplomatic hand would be strengthened when it would seek a similar favour from some of the countries to which it is showing a degree of generosity,” said Sibal.

Meanwhile, India’s former ambassador to the US, Lalit Mansingh, said at this point, diplomacy should not be discussed in transactional terms.

“When a country makes an appeal for drugs in this kind of calamity, humanity remains the foremost priority in the decision making. It is not about taking advantage of a particular country in a crisis. Right now, it’s the humanitarian sentiment that is uppermost,” Mansingh told Al Jazeera.

He claimed that India has not deviated from its policy to help those in need, especially in the pharma sector.

“As a fact, India has a policy of helping like it did in the case of HIV/AIDS. Drugs made in India helped millions of lives in Africa,” he said.

Pharma industry hit by pandemic

India is the largest producer of generic drugs and has, over the years, made the cost of treatment much cheaper for people all over the world.

According to Global Business Reports, “The generic drugs industry continues to strengthen itself as a key pillar of India’s burgeoning economy. As the largest provider of generics in the world, the sector contributes to 40 percent of the United States’ generic demand with Indian companies receiving 304 Abbreviated New Drug Application approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017. Moreover, the industry exports to almost every nation, and has significant footprints in all the highly-regulated developed markets.”

India is home to the third-largest pharmaceutical industry in the world in terms of volume and 10th-largest in terms of value.

The total size of the industry, including drugs and medical devices, is approximately $43bn of which it exports $20bn worth of drugs. The pharmaceutical sector currently contributes about 1.72 percent to India’s gross domestic product (GDP).

India exports pharma products to more than 200 countries, including heavily regulated markets in the US, Western Europe, Japan and Australia.

However, with businesses across the globe taking a major hit because of the pandemic, Indian pharma sector, too, is not untouched by the crisis.

The spectre of coronavirus has exposed the chinks in India’s pharmaceutical sector which is struggling to ramp up production due to its overreliance on China for active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and other bulk drugs which are key ingredients of the finished formulations.

“Last year, the country imported roughly 50,000 crore rupees ($6.5bn) worth of API and other intermediaries that go into production of finished formulations,” said Dr Saktivel Selvaraj of the Public Health Foundation of India.

“About 31,740 crore rupees ($4.1bn) [worth of API] were from China alone, accounting for two-thirds of API imports.”

A large section of these APIs is are imported from the Hubei province of China, which is believed to be the origin of the new coronavirus and a manufacturing hub of API and other bulk drugs.

Over the years, India’s dependency on China has increased substantially since Indian pharma companies found it cheaper to import than to manufacture the key ingredients.

Meanwhile, domestic drug manufacturers have claimed that if the government did not intervene soon, the consumer would start feeling the pinch of the shortage of API, as many essential drugs could disappear from shelves in the next few weeks.

Manav Grover, managing director of Cosway Pharmaceutical, which manufactures more than 200 drugs, including painkillers, antibiotics and other medicines, said the company’s stocks are depleted and the cost of raw materials has skyrocketed in the last few weeks, especially after imports from China were stopped due to the spread of the coronavirus.

According to him, the end consumer will start to feel the heat of this shortage very soon.

“Suppliers are hoarding raw materials and have increased the price manifold. The situation is really bad, there is so much black-marketing. Even those raw materials which were easily available are being hoarded by traders,” Grover told Al Jazeera.

“Just like masks and hand sanitisers, raw materials too are not easy to find. For instance, we used to get HCQ for 20,000 rupees ($261) a kg but the rate is now 85,000 rupees ($1,111) a kg. So, production of one HCQ tablet cost the manufacturer five rupees ($0.06) earlier, it costs 35 rupees ($0.45) now.”

[source: aljazeera]