You may lather it into your scalp, smear it on your lips, or rub it into your face every day, but that doesn’t mean your shampoo, lipstick, or moisturizing cream has ever been checked for safety—at least not if you live in the US. In fact, the US Food & Drug Administration, the federal agency responsible for regulating the cosmetic industry, is mostly toothless when it comes to making sure skincare and hair products are safe.

The FDA doesn’t have the power to require companies to disclose their full ingredient list, report complaints, or safety-test products before they go to market. It can’t even force a company to recall a product if problems are found. The US bans or restricts 11 ingredients from cosmetics, but for comparison, Canada bans 587. The European Union, which requires pre-market safety testing, bans 1,328.

In the US, “you can develop a cream tonight, and sell it tomorrow,” says Shuai Xu, a dermatologist at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “Overall, cosmetics are very safe. But over the last 10 years, we’ve had controversy after controversy—mercury in skin lightening creams, for example, or Brazilian blowouts,” Xu said, referring to the hair-straightening treatment that, when combined with the heat from a straightening iron, releases the toxin formaldehyde. “It’s a slippery slope.”

Just last year, the FDA began putting complaints it’s received from the public about cosmetics on a website anyone can access. In a letter published Monday (June 26) in JAMA Internal Medicine, Xu and his colleagues combed through the FDA’s new Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s Adverse Event Reporting System and found complaints more than doubled between 2015 and 2016, with most of the increase coming from issues reported about haircare products.

They also found that when it came to the severity of complaints, the products most associated with “serious” health effects (defined by the researchers as “serious injury, disability, congenital anomaly, or death”) were baby products like baby shampoos and lotions. Just over half of all baby product complaints were classified as “serious.”

The researchers note that their research is limited due to the fact that the health outcomes were self-reported, and toxicology data for most products simply doesn’t exist, because it isn’t required. “The FDA has minimal oversight, but also just minimal data. We don’t know exactly what is causing these complaints,” Xu said. “At the very least, we need broader participation in the database [from manufacturers].”

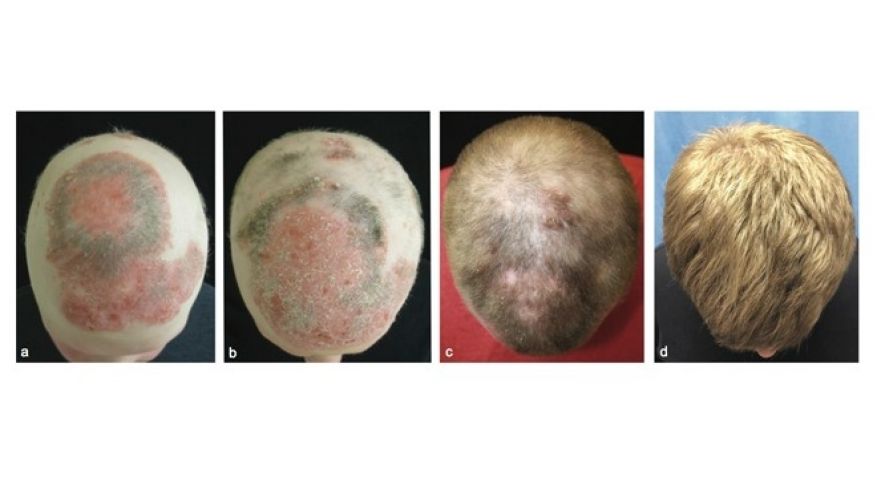

The big uptick in haircare complaints was caused primarily by the Los Angeles hairstylist Chaz Dean’s line of “Wen” cleansing conditioners. “The controversy is still ongoing—the product is still on the market,” Xu says. “It’s a great index case; it really underscores the problems we have in the US.” With varieties like sweet almond-mint and lavender, the conditioners are marketed as being free of harsh chemicals. But they made people’s hair fall out; in one case, a 9-year-old girl in Denver, Colorado lost all her hair after three washes with the conditioner in 2014. The FDA launched an investigation that year after receiving 127 complaints about the products, only to find that the company had received more than 21,000 complaints about itching scalps, rashes, and sudden balding dating back to 2011. Unlike the pharmaceutical industry, cosmetics manufacturers are not required by the FDA toreport complaints about their products to the agency.

What’s more, the FDA can only take legal action against a company if it violates a law, by mislabeling a product, for example, or if a product is found to have been contaminated by some illegal ingredient. In an event where a product is causing harm to consumers but is technically legal, the FDA is hamstrung. Wen cleansing conditioners still remain on the market, and a spokesperson for Guthy-Renker, the distributor of Wen, said in an email that “there is no credible evidence to support the false and misleading claim that WEN products cause hair loss.”

Guthy-Renker belongs to the cosmetics trade association Independent Cosmetic Manufacturers and Distributors, which has lobbied against legislation introduced by senator Dianne Feinstein in 2015 that would strengthen the FDA’s ability to regulate their industry. Current regulations are based on two pages of text in a 1938 law that hasn’t been meaningfully updated, and which left the industry virtually unregulated. In their letter in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers urge passage of that legislation. The bill would give the FDA the ability to force product recalls, and compel the agency to review five different ingredients a year for safety.

But, the researchers say, even that wouldn’t go far enough: The US should take a page from European standards and actually test products before they go on the market, they write.

[“source-qz”]