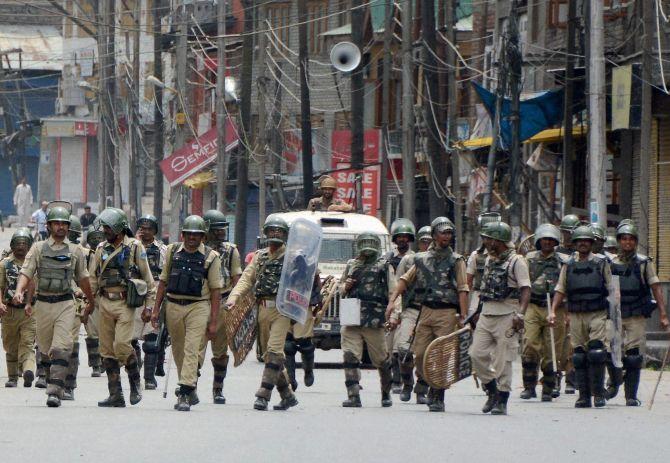

Curfew was lifted on Thursday, July 28, from across Kashmir, barring Anantnag town, following improvement in the situation in the aftermath of the violent clashes that broke out after Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani was killed on July 8.

Radha Kumar was one of the interlocutors appointed by the United Progressive Alliance government on Jammu and Kashmir in 2010, after at least 120 youth were killed in clashes with security forces.

Kumar, below, left, tells Aditi Phadnis what India should do for the state where 47 people have died in the last month alone.

You were part of a committee appointed by the UPA government on Kashmir. You conducted extensive interviews and made several recommendations which, if they had been followed, could have brought some semblance of normalcy to the state. Tell us what the report said.

We were appointed at a terrible moment for the Kashmir Valley, when close to 120 youth had died. Our task was to engage with all sections in the state and suggest both short-term and long-term measures to end the conflict.

We visited all 22 districts in the state and met government and civil society representatives across the opinion spectrum. We also sought inputs from people residing in Pakistan occupied Kashmir, who have their own grievances.

The key conclusion of the report: Though the Kashmir Valley had pulled back from the brink of greater conflict, the situation remained volatile with the youth likely to erupt again and perhaps take to the gun.

Therefore, a renewed peace process was urgently required, beginning with a series of political, security, human rights and economic confidence-building measures.

Is a new Kashmiri militant on the rise? If so, why has the youth opted for militancy?

There is a new Kashmiri militant insofar as it is a new generation of youth that is picking up the gun. Like the earlier generation, some are educated but most only partially (the recently slain Burhan Wani dropped out in Class 10 to become a militant).

They also seem to be younger than the earlier generation of militants when the latter picked up the gun. They are using social media for recruitment and publicity — something the earlier generation did not have access to.

This new wave of militancy has elements of Islamic militancy and is also a protest against the Indian State. As interlocutors we held a meeting with the youth in Sopore.

I was struck by how little they knew about Kashmiri Islam; for them, Wahhabi Islam was the one true path. On the other hand, very few Kashmiri militants or their supporters call for a caliphate; Unlike Islamic State, they have not yet filmed themselves in acts of gross brutality, though they have engaged in them, for example, by murdering sarpanches.

Why is the Kashmiri youth opting for militancy once again?

What happened in 2010 could be a reason: Seeing 120 youngsters like themselves die could have pushed some of them over the edge, given that there are active recruiters for militancy all over the valley. But at present the number of youth taking up militancy is still relatively small.

The real problem is the swell of street militancy — stone throwers and their supporters. Public support for militants and protesters had dropped to a trickle; now it appears to have spread throughout south Kashmir and even parts of Doda and Kishtwar.

For us, as Indians, the most important issue should be to recognise and amend the behaviour of the Indian State, including its image in the valley. The death of at least 30 Kashmiris and injuries to hundreds of others, including poilcemen, should be unacceptable.

Those who ask why Wani was allowed a public funeral when he had killed Kashmirisarpanches have a point; but those who ask why the police were not equipped to better deter angry mobs have an equally strong, if not stronger, point.

When we wrote the report in 2011, we opened by saying that we should resolve that such deaths would never happen again. But six years later we seem to be there again.

Kashmir has a legislature. It has panchayats and local self governance. It has members of Parliament and Union ministers. How much autonomy is enough autonomy?

Kashmir has a legislature. It has panchayats and local self governance. It has members of Parliament and Union ministers. How much autonomy is enough autonomy?

Panchayats are not an issue of autonomy; they are an issue of governance. The Panchayati Raj institutions have not been empowered yet, though the elections took place six years ago. This is a massive failure of the state government. More than 20 sarpanches have been killed by militants.

The government cannot protect all 30,000 sarpanches, but it can empower them to carry out their duties. If they are seen to perform, local support will offer them protection.

Regarding the legislature and elected government, we have a long history of New Delhi’s political ‘interference’ — from the imprisonment of Sheikh Abdullah when he was chief minister to the propping up of proteges rather than accountable governments.

For the past 28 years, the state has been in a situation of both cross-border and internal armed conflict, in which the first casualties have been the institutions of governance.

The state is dependent on New Delhi for economic aid as well as security. In such a situation, democracy does not hold sway, either between the people and the state government or between New Delhi and Srinagar, and the state is seen as being ruled by New Delhi, not by its own elected government.

Regional political parties such as the National Conference have a long list of areas in which the original autonomy provisions of the Indian Constitution as well as the state constitution have been rolled back.

I believe that many of those provisions are no longer valid, but there has never been a free and frank discussion between the state and the central leadership on whether the amendments/rollbacks were necessary and acceptable.

Some of these issues have been dealt with in the Agenda of Alliance of the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Peoples Democratic Party, but no action has been taken on them.

In the current geopolitical situation — different locii of power in Pakistan, disturbances in Afghanistan, and the rise of Daesh (Islamic State) — where do you see militancy in Kashmir heading?

In the immediate sense, Pakistan will continue to seek turmoil and violence in the Valley.

The different locii of power in Pakistan do not really matter as far as we are concerned, as the Pakistan military are in charge of India policy and thus far no civilian leader has been able to change that equation; Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is not even trying.

The rise of Daesh and the situation in Afghanistan both have an impact.

It should be of concern that some youth in Kashmir have started raising Daesh flags along with those of Pakistan.

More importantly, it was already forecast that the drawdown in Afghanistan and the pressure that would then fall on Pakistan to deliver the Taliban to peace talks might lead that country to escalate cross-border militancy.

However, let me stress again that we can marginalise Pakistan if we ourselves take the political healing touch and security steps required. Pakistan acquired a foothold in the valley due to our omissions in the 1980s.

Having compounded those omissions exponentially in the years that followed, the task of getting Pakistan out is far more difficult than before.

We have a strength that we have failed to use adequately: The fact that there is great disaffection in Pakistan-held Jammu and Kashmir (especially in the Neelum valley and Baltistan) due to the coercive policies of the Pakistan government.

Highlighting Pakistan’s own behaviour and the need to address grievances there will, over time, lead Pakistanis to de-escalate their Kashmir policy. This was one lever that worked during the 2004-2007 period.

[source;rediff.com]