Abiraterone, for instance, is a drug used to treat metastatic prostate cancer. The Food and Drug Administration initially approved it in 2011 to treat patients who failed to respond to previous chemotherapy. It does not cure anyone. The research suggests that in previously treated patients with metastatic prostate cancer, the drug extends life on average by four months. (Last year, the FDA approved giving abiraterone to men with prostate cancer who had not received previous treatment.) At its lowest price, it costs about $10,000 a month.

Abiraterone is manufactured under the brand name Zytiga by Johnson & Johnson. To justify the price, the company pointed me to its “2017 Janssen U.S. Transparency Report,” which states: “We have an obligation to ensure that the sale of our medicines provides us with the resources necessary to invest in future research and development.” In other words, the prices are necessary to fund expensive research projects to generate new drugs.

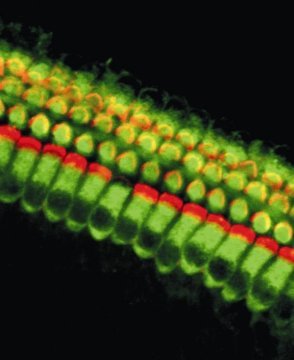

This explanation is common among industry executives. To many Americans, it can seem plausible and compelling. It’s easy to conjure images of scientific researchers in their protective gear and goggles carefully dropping precious liquids into an array of Erlenmeyer flasks, searching for a new cure for cancer or Alzheimer’s. But invoking high research costs to justify high drug prices is deceptive.

No matter the metric, drug prices in the United States are extreme. Many drugs cost more than $120,000 a year. A few are even closing in on $1 million. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that Americans spent more than $460 billion on drugs—16.7 percent of total health-care spending—in 2016, the last year for which there are definitive data. On average, citizens of other rich countries spend 56 percent of what Americans spend on the exact same drug.

Read: The 7 most revealing moments from a major drug-pricing hearing

Excessive drug prices are the single biggest category of health-care overspending in the United States compared with Europe, well beyond high administrative costs or excessive use of CT and MRI scans. And unlike almost every other product, drug prices continue to rapidly rise over time. HHS estimates that over the next decade, drug prices will rise 6.3 percent each year, while other health-care costs will rise 5.5 percent. Basic economic principles suggest that drug prices should be going down, not up: For most drugs, manufacturing volumes are increasing, and little new research is being conducted on those already on the market.

Reducing these high drug prices has become a major political concern—and a rare bipartisan cause for Democrats and Republicans to rally around, albeit with disagreement about how to actually get it done. In his State of the Union address last month, President Donald Trump called the price discrepancy between the United States and other countries “unacceptable” and “unfair,” and vowed to “stop it fast.” In a Senate Finance Committee hearing on drug pricing a few weeks later, Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon compared the way the drugmaker AbbVie protects the exclusivity of one of its drugs to the way Gollum protects his ring.

Yet every time Congress debates doing something about drug prices, the industry—and the advocacy groups it funds—vociferously returns to the point that lower prices will thwart innovative research. The fear of missing a cure for Alzheimer’s or Lou Gehrig’s disease or depression contributes to stalling reform. But there are many reasons to question the widely held notion that high drug prices and innovative research are inextricably linked.

The most telling data on a disconnect between drug prices and research costs have received almost no public attention. Peter Bach, a researcher at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and his colleagues compared the prices of the top 20 best-selling drugs in the United States with the prices in Europe and Canada. They found that the cumulative revenue from the price difference on just these 20 drugs more than covers all the drug research and development costs conducted by all the drug companies throughout the world—and then some.

To be more precise, after accounting for the costs of all research—about $80 billion a year—drug companies had $40 billion more from the top 20 drugs alone, all of which went straight to profits, not research. More excess profit comes from the next 100 or 200 brand-name drugs.

If you watch television, you know part of the answer to where this extra money is going: sales and advertising. Of the 10 largest pharmaceutical companies, only one spends more on research than on marketing its products. But it’s hard to figure out what it actually costs drug companies to conduct the research required to get FDA approval and bring a single drug to market. The pharmaceutical industry and its advocates tend to peg the cost of creating and bringing to market just one new drug at $2.6 billion. This figure comes from a cost report published in October 2016 by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development.

There are several reasons to suspect that number is unreliable. According to the Tufts Center’s website, more than a quarter of its budget comes from“unrestricted grants” from pharmaceutical companies and their partners. And no one can verify Tufts’ analyses and claims: The authors say the data come from research spending on 106 drugs produced by 10 of the top 50 multinational pharmaceutical companies, but the underlying data are deemed proprietary and confidential.

Tufts also uses a cost-accounting methodology that appears to significantly inflate its estimate. About 45 percent of Tufts’ $2.6 billion figure is attributed to the amount companies would pay to lenders and shareholders for the capital they invest in research. Tufts uses an interest rate of 10.5 percent a year, but investment bankers tend to use just 6 percent in their economic models. That one change would reduce the Tufts estimate by about a quarter of its total figure. That’s not to mention other factors the Tufts team leaves out that reduce the cost of drug development, such as tax credits the federal government offers for research and development.

When asked about these issues, the report’s chief author, Joseph DiMasi, noted that one other study with public data, published in 2009, comes to similar results. He argues that even if we exclude the cost of capital, $1.4 billion per FDA-approved drug is a high price—and the cost has been growing at about 8.5 percent annually.

Pharmaceutical companies often claim that the research costs of unsuccessful drugs also have to be taken into account. After all, 90 percent of all drugs that enter human testing fail. But most of these failures occur early and at relatively low costs. About 40 percent of drugs fail in preliminary Phase I studies, which assess a drug’s safety in humans and typically cost just $25 million a drug. Of the drugs that clear this first phase of testing, about 70 percent fail during Phase II studies, which assess whether a drug does what it is supposed to do. The research costs of these studies are still relatively low compared with overall R&D costs—on average, under $60 million a study.

The 2017 JAMA Internal Medicine study incorporated all research costs on drugs not yet on the market into its final calculations. The pharmaceutical companies it examined had an average drug success rate of 23 percent, which the Tufts researchers argue is too high to accurately represent the amount of money that failed drugs would usually add to a company’s research costs. But cancer drugs, specifically, do have a success rate of 20 to 25 percent—so the selection of only successful companies does not seem to be the difference.

Joaquin Duato, the vice chairman of Johnson & Johnson’s executive committee, argues that critics fail to deal with the realities of drug R&D. He told me that last year, Johnson & Johnson had $41 billion in prescription-drug sales, of which $8.4 billion went to R&D and $4.5 billion went to sales and marketing. Other costs included manufacturing, finance, IT, taxes, and more. This funds research on 100 candidate drugs, which result in one or two FDA approvals a year. “For drug companies, the return on capital is in the mid-teens, which is nowhere near tech-company returns,” Duato said.

Nevertheless, some former pharmaceutical-company executives say that research costs do not determine drug prices—and they explain how. In his book A Call to Action, Hank McKinnell, a past CEO of Pfizer, wrote under the heading “The Fallacy of Recapturing R&D Costs”:

How do we decide what to charge? It’s basically the same as pricing a car … A number of factors go into the mix. These factors consider cost of business, competition, patent status, anticipated volume, and, most important, our estimate of the income generated by sales of the product. It is the anticipated income stream, rather than repayment of sunk costs, that is the primary determinant of price.

Raymond Gilmartin, a former Merck CEO, once said to The Wall Street Journal: “The price of medicines is not determined by their research costs. Instead, it is determined by their value in preventing and treating disease.”

Exorbitant drug prices have two bad effects. First, high costs mean that lots of patients are unable to take their medications. A recent study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology assessed patients’ access to 38 different oral-cancer drugs and found that 13 percent of cancer patients did not buy approved chemotherapy drugs if they had a co-payment of $10 a month, while 67 percent did not when they had to pay $2,000 or more.

Second, the high drug prices distort research priorities, emphasizing financial gains and not health gains. Cancer drugs are routinely priced at about $120,000 to $150,000 a year, and more than 600 cancer drugs are now being tested on humans. This can lead to great societal benefits: The United States is expected to face 1.76 million new cancer cases and more than 600,000 cancer deaths in 2019 alone. But many of the drugs that companies are pursuing have low promise, where the health gains are small—weeks of added life, not big cures. While even this short extra time can be valuable to individual families, too much investment in oncology means not enough in drugs for other illnesses whose treatments cannot be so highly priced.

Read: Big Pharma gets a big win from Trump

Consider antibiotics. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks antibiotic-resistant infections as one of the nation’s top health threats. An estimated 2 million Americans become infected with such bacteria each year, and 23,000 die. A superbug that is resistant to all known antibiotics is an imminent threat. Yet because antibiotics are generally cheap, for most pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies they are not a primary focus. The Pew Charitable Trusts reports that only about 41 new antibiotics with the potential to treat serious bacterial infections were in clinical development for the U.S. market in March 2017.

The simple explanation for excessive drug prices is monopoly pricing. Through patent protection and FDA marketing exclusivity, the U.S. government grants pharmaceutical companies a monopoly on brand-name drugs. But monopolies are a recipe for excessive prices. A company will raise prices until its profits start to drop.

To address the problem of high prices and reduced access to drugs, Johnson & Johnson advocates eliminating rebates to pharmacy benefit managers and insurers, which would increase price transparency and lower patient co-pays. But it would not necessarily lower total drug prices. The proposal avoids the standard economic response to monopoly pricing: price regulation. Every other developed country regulates drug prices, often through price negotiations pegged to cost-effectiveness analysis or some other measure of clinical benefit.

Will R&D go down if the United States follows this model? Not necessarily. Remember, the high drug prices fund R&D but also marketing, manufacturing, administrative expenses, and profits at the companies. Lower revenue from lower drug prices could reduce marketing, administration, and excessive profits before R&D costs have to be reduced.

Where cuts are made is up to drug companies. Their claims of lower R&D costs appear designed to generate fear, but as some former executives themselves have acknowledged, there is no necessary link between a decline in drug prices and a decline in R&D. Drug companies could make other choices that maximally improve the health of all Americans.

[“source=theatlantic”]